|

Winter 2006

(14.4)

Pages

54-57

Underwater

Archaeology in the Caspian

Past,

Present and Hopefully Future

by Zhenya Anichenko, Certified Scuba Diver

Zhenya Anichenko

[pronounced "a-ni-CHEN-ko"] was so captivated by legends

that described submerged monuments in the Caspian that in the

summer of 2006 she made her way from Alaska to Azerbaijan in

quest of learning more. Zhenya Anichenko

[pronounced "a-ni-CHEN-ko"] was so captivated by legends

that described submerged monuments in the Caspian that in the

summer of 2006 she made her way from Alaska to Azerbaijan in

quest of learning more.

Zhenya, a certified scuba diver,

came in search of the Viktor Kvachidze who had initiated underwater

archaeological exploration and research in the Caspian in the

1960s.

Fortunately, she succeeded in finding him - a historian and maritime

archaeologist who for the past 30 years has been working with

Azerbaijan's History Museum under the auspices of Academy of

Science. Unfortunately, she discovered that underwater archaeology

had come to a grinding halt with the collapse of the Soviet Union

15 years earlier.

Zhenya dreams of the day when research will start again and Azerbaijani

scientists will have the equipment and training to pursue their

quest in unlocking some of the mysteries that lie at the bottom

of the sea.

She dreams of becoming involved as well. She's convinced that

the technological basis for such maritime research might be readily

available in the region especially since oil companies possess

sophisticated equipment for survey of underwater natural resources,

some of which she is convinced could also be used for locating

cultural resources.

She believes that cooperation between these two sectors could

lead to the establishment of a Center for Underwater Archaeological

Research and Cultural Resources Protection. If such a center

could be established, it would be the very first submerged heritage

center in the entire Caspian region.

Ancient History

Located on the periphery of European civilization, the Caspian

Sea has, for centuries, been veiled in mysteries and legends.

Assyrians believed that this vast body of water was the home

of the sun from whence it rose every morning and to which it

returned to rest at night.

Ancient Greek geographers argued about whether the Caspian was

a land - locked body of water or a gulf of the Northern Ocean.

Medieval authors spared no ink describing the fierce local tribes

of Gog and Magog, who had been defeated and locked behind iron

gates by Alexander the Great until Doomsday when they would return

to destroy the world.

In the 19th century, heated scientific discussions arose around

the issue of whether the great Asian river Amu Darya1 had ever flowed into the Caspian Sea2 and thus provided a navigable route

to rich outposts of Central Asian trade located in Khiva3 and

Bukhara4.

Today, we know a lot more about the Caspian Sea. Its geography,

hydrographic characteristics and natural resources have been

the topics of thorough research for decades. Still the sea has

not yielded up many of its mysteries. Lost ships and forgotten

cities still lie submerged beneath Caspian waves, awaiting explorers

to reveal their secrets.

The Caspian is the largest inland body of water on Earth. It

extends from the marshy delta of the Volga River in Russia in

the North to the coast of Iran in the south, from the mountain

ranges of the Northern or Great Caucasus of Azerbaijan in the

west to the Turkmen and Kazakh deserts in the east. Essentially,

some would argue that the Caspian is the world's largest lake.

Long and relatively narrow, it extends 1,200 km (745 miles) north

to south and 320 km (210 miles) east to west.

Shallow along the northern shores,

the sea deepens towards the south, reaching its maximum depth

at about 1,025 meters (3,363 ft). Its north-south orientation

and the significant depth variation create rich and diverse ecosystems

and contribute to the wealth of the sea's biological resources,

which have attracted people to settle along its shores for millennia.

Names Through History

Throughout history people living along the coasts of the Caspian

and the foreigners who came to the region either by trade or

military exploits have referred to this great body of water by

various names: Hirkanian, Khazarian, Khvalynian, Caspian, Mare

Corvzum and Mare de Bachu.5 Each name bears historical reference

to a country or nation that once flourished there. An early region

of habitation for man, the Caspian coastal plains are lands where

many ancient civilizations originated, mingled and sometimes

even clashed with one another.

The sea was generous to the

people. It provided an abundant source of seafood, salt and oil,

not to mention one of the most convenient modes of transportation.6 It also contributed to the rise of

local economies and cultural exchange. However, these benefits

came with a price tag.

Sea Level Fluctuation

Isolated from the world ocean, the Caspian is known for its dramatic

fluctuation in water level. Its current level is 28 meters below

absolute sea level.

Analysis of geomorphologic and

historic data over the period from the first century AD to the

beginning of the third millennium shows seven periods of significant

Caspian sea level rise, each followed by a regression. According

to Yu. A. Karpychov, levels of the Caspian Sea peaked during

the 1st, 3rd, 6th, 9th, 14th, 17th and 19th centuries AD.

The time lapse between periodic sea level peaks averaged between

200-280 years. These variations dramatically affected the history

of local states. Like an invincible invader, the quiet power

of the sea conquered fortresses and cities without the use of

a single arrow or bullet. One of the longest sea level regressions,

for example, lasted more than 400 years, only to reverse itself

at the close of the 15th century and rise nearly seven meters

higher than the high level recorded in 1999.7

Though not a flood of Biblical proportions, this course of natural

events brought about significant changes for the people living

along the seacoast. Advancing waves claimed many coastal communities

and put an end to a half-millennium old pattern of habitation,

giving literal meaning to the expression "the tides of history".

Legends of the

Caspian

The unique cyclical pattern in the variation of the sea level

of the Caspian has fostered numerous legends, historical accounts

and theories regarding the inundated sites of the territory.

Many believe that countless mysteries of the region are located

at the bottom of the Caspian Sea.

For example, according to some people, off the coast of Northern

Dagestan lies the third and last capital of Khazar Khaganat,

the fabled city of Itihl, which flourished from the 9th to 12th

centuries CE, and then mysteriously vanished from historical

accounts.8

Further south along the Caspian coast, the city of Derbent [Darband

in Azeri]9

presents another enigma.

According to some medieval chronicles, one of its walls stretched

300 meters into the sea. Why and how it was built remains a subject

of discussion. Legends credited its construction to giants. Historians

argue whether it was an element of harbor fortification, a medieval

marina, or just a city wall claimed by the rising sea

Sabayil Castle

Down along the coast of Azerbaijan, similar discussions surround

a site in the Bay of Baku, known as Sabayil Castle or Bayil Rocks.10 This 14th century structure, whether

a fortress, castle, caravanserai or, perhaps, even a residence

belonging to the Shirvan Shah, now lies completely submerged

and has prompted many interpretations. But its mysteries caught

my imagination for a different reason.

Quite accidentally, I chanced upon a description of Sabayil published

in a 19th century issue of Naval Digest. Like all true passions,

this new obsession to understand more about underwater archaeology

in the Caspian was extremely untimely as it took place in the

fall of 2003 when I was on a research expedition to St. Petersburg,

looking for the materials about a Russian-American Company sailing

ship called Kad'iak.

The scientists with whom I was working at the time had discovered

the shipwreck just a month earlier, and we were preparing for

the first archaeological season on site. It was to be the first

underwater archaeology project undertaken by the state of Alaska

where I was working at the time.

But it wasn't just Sabayil Castle that became a consuming passion

but the very thought of getting a chance to investigate submerged

lands and their archaeological potential for the Caspian and

the history of the region.

Excited and overwhelmed with the sense of responsibility for

this research in Russian literature, I had only two weeks to

sieve through countless archival records and old publications

in search of construction details for the ship, the crew's personal

records and any other potentially useful information.

Yet, despite the heavy workload, I could not stop thinking about

the material that I had accidentally read about Baku's Sabayil

Castle. The article was a matter-of-fact description of the 14th

century "caravanserai" that lay submerged beneath the

sea in the Bay of Baku. Several drawings had accompanied the

text.

By that time, I had been certified as a scuba diver for three

years. A few months earlier I had completed my Master's degree

in Underwater Archaeology at East Carolina University in Greenville,

North Carolina, which is one of only three universities that

offers such a program in the United States.

No Caspian Maritime

Studies

My curriculum had included many classes on the theory and history

of Underwater Archaeology and Maritime History throughout the

world. We had examined projects in many countries and discussed

the potential of underwater archaeology around the globe. However,

the topic of the Caspian Sea had never arisen in any of these

discussions. Yet, my very first, quite accidental, encounter

with the topic made it clear to me that the investigation of

submerged cultural heritage in the Caspian Sea was very important,

not to mention, so tantalizingly promising.

Searching for information about underwater research in the Caspian

Sea proved to be difficult. None of the major Underwater Archaeology

Bibliographies or on-line databases provided anything on the

topic, and none of my American and European colleagues could

help me in this search. When researching the literature written

in Russian, I came across many books and articles on the history

of lands around the Caspian, but very few of them dealt with

the history of seafaring.

It took such a long time before I found anything about underwater

Caspian research. I began to wonder if it really could be that

the ever-growing diving community was simply not aware of the

Caspian Sea's potential with its unique physical characteristics

and rich historical legacy. Might the Caspian be the last sea

in the world that had not yet been discovered by maritime archaeologists?

Viktor Kvachidze

I found that hard to

believe, and one lucky day my skepticism was rewarded. I discovered

that the Caspian, indeed, had its own Underwater Archaeologist.

It was Viktor Kvachidze [pronounced kvah-CHID-zeh] who had been

working at Azerbaijan's Museum of History in Baku for more than

30 years, many of which had been dedicated to underwater diving

expeditions and research.

Once I had identified

his name, my search suddenly became much easier. Once I had identified

his name, my search suddenly became much easier.

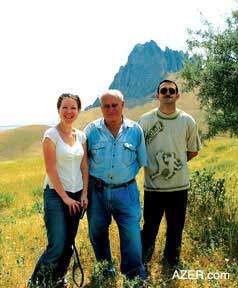

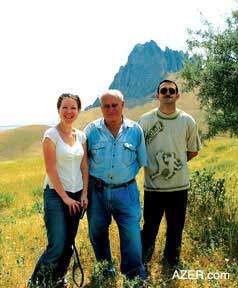

Left: After extensive research on the

Internet, Zhenya Anichenko (left) a maritime archaeologist and

scuba diver who lives in Alaska finally got the chance to go

to Baku to meet Viktor Kvachidze, archaeologist and historian

who organized the first underwater archaeological expeditions

in Soviet Azerbaijan in the Caspian in the late 1960s. Photo:

June 2006

From on-line newspapers and magazines, I learned about some

of Kvachidze's fascinating projects, which included archaeological

sessions related to Sabayil and the inundated medieval settlements

of Bandovan, surveys of the Absheron Peninsula near Baku, an

investigation of Stepan Razin's camp on Svinoi Island and much

more. As pioneering work, each of Kvachidze's projects was an

important breakthrough. Each one opened new horizons and offered

new perspectives.

Because of Kvachidze's research, we now possess knowledge that

the coastal waters of Azerbaijan are, indeed, rich with submerged

sites and ancient material culture.

This very knowledge provides the impulse for the development

of Underwater Archaeology, not only in Azerbaijan, but also in

other countries that border the Caspian.

This is especially important now that the Caspian states are

re-emerging after the collapse of the Soviet Union [late 1991],

and are making decisions regarding the common use of the sea's

rich resources, especially petroleum and caviar from sturgeon.

Viktor Kvachidze's work is an essential contribution towards

a more secure future of fascinating underwater sites of Azerbaijan,

both those which have been identified and those yet to be discovered.

His research and enthusiastic articles make people aware of the

importance of the country's submerged cultural heritage, which

is the first and, perhaps, the most important step towards ensuring

its protection.

During the Soviet period (1920 - 1991), laws governing the use

of the Caspian basically had to be resolved between two countries-the

Soviet Union and Iran. Today, five countries must sign off on

them: Azerbaijan, Russia, Kazakhstan, Turkmenistan and Iran.

So joint cooperation is much more cumbersome.

Just like any other biological and natural resource, the submerged

cultural heritage is fragile and irreplaceable. This cultural

heritage needs consistent and thoughtful protection because coastal

and maritime industries, which are the cornerstones of many Caspian

states' economies, are so vulnerable.

Journey to Baku

Very few people in the history of the discipline of Underwater

Archaeology can claim the achievements of such monumental importance

as can Kvachidze. It takes courage, erudition, curiosity, charisma

and, above all, tireless persistence to pioneer in a field of

human knowledge. Kvachidze, as I came to realize during my short

visit to Baku in June 2006, was the embodiment of all these traits.

His generous attention made my trip unforgettable.

There I was, having arrived in Azerbaijan - an unknown country

to me - full of great expectations along with advice for "worst-case

scenarios". My friends and relatives, who were both horrified

by the perspective of my traveling alone to Azerbaijan as well

as puzzled about my motives, had liberally proffered all kinds

of cautious advice. It's easy to understand their concerns, given

the fact that at the time I was currently residing on a small

island off the coast of Alaska.

The trip to Baku proved difficult: it required five connecting

flights and three days of travel just to meet a person whom I

only knew from reading academic publications. My reasons, I thought,

were quite justifiable. Here was a chance to meet the man who

had initiated the study of Underwater Archaeology in the region.

Finally, I would have a chance to ask him questions face to face.

And, at last, I would be able to visit the country I had been

reading about during every spare moment over the last several

years.

Those 10 days this past summer 2006 in Azerbaijan far exceeded

my expectations. Walking through Baku's Old City and traveling

throughout the countryside with Kvachidze offered a superb introduction

to the history of Azerbaijan and to the current situation in

underwater research.

I learned that Underwater Archaeology in Azerbaijan had gotten

off to an exciting start in the late 1960s, but that after several

decades of steady work, it had nearly fizzled out. With Azerbaijan's

independence from the Soviet Union, suddenly they had been cut

off from adequate funding to continue carrying out the underwater

expeditions. In reality, as a consequence, qualified personnel

in Underwater Archaeology have been deprived of the chance to

carry out scientific fieldwork since 1986.

More importantly, the younger generation of local Underwater

Archaeologists have not yet emerged or even been trained. Azerbaijan,

like all of the former Soviet Union republics, with the exception

of Ukraine and Estonia, has no university program in this discipline.

Restarting Underwater

Research

Starting such a program is an enormously difficult task in a

country where, until recently, there has not even been a single

recreational dive shop. The cost of equipment, lack of the faculty

with appropriate credentials, and the concerns regarding whether

such a program would attract a sufficient number of students

are all valid considerations that have put the creation of such

a program on hold. Yet, there is hope that the study of Azerbaijan's

submerged cultural heritage will be able to reach an exciting

new level.

Kvachidze's work in the past demonstrated that many cultural

and research institutions of the country, including the Azerbaijan

Academy of Science and the Ministry of Ecology have recognized

the value of underwater research. While these organizations might

lack funds and necessary technology, they provide an academic

context and are in a great position to continue advocating further

research and protection.

The technological basis for such underwater research might also

be readily available in the region: oil companies possess sophisticated

equipment for survey of underwater natural resources, some of

which could also be used for locating cultural resources.

Left:

Early maritime archaeological expeditions carried out by Victor

Kvachidze near the Shulan Bay (northern coast of Absheron), 1969 Left:

Early maritime archaeological expeditions carried out by Victor

Kvachidze near the Shulan Bay (northern coast of Absheron), 1969

An ideal situation would foster the cooperation between these

two sectors, which could result in the establishment of a Center

for Underwater Archaeological Research and Cultural Resources

Protection, which would be the very first submerged heritage

center in the entire Caspian region.

The experience of other countries shows just how important such

a center could be for the development of maritime research.

The Maritime Museum of Bodrum

in neighboring Turkey, which was founded about 20 years ago,

has developed into one of the most popular museums in the country.It

also has become a research center providing a center for many

famous underwater discoveries in the Black and Mediterranean

Seas.

Establishing an efficient and comprehensive program for the research

and protection of maritime cultural resources will take time,

commitment, effort and funding. A task of such magnitude is not

likely to be possible without the cooperation between many national

and international institutions. It would take a tremendous effort

to launch such a project but the benefit would be enormous in

reawakening an awareness of history of the region.

There are countless secrets that only the sea can yield to modern

historians, ecologists and archaeologists from the pattern of

early medieval coastal settlements to the medieval traditions

of Caspian shipbuilding and ancient maritime trade. There is

so much hope that the great achievements of underwater research

in Azerbaijan can, indeed, be re-established. The time is now

since those who have made initial explorations in the Caspian

like Viktor Kvachidze are still here with us to share their knowledge

and expertise.

Zhenya Anichenko has a Master's

degree in medieval history (Central European University in Budapest,

Hungary). On her honeymoon, husband Jason took her to Belize

where they got certified in scuba diving. She found the warm

water coral reefs with their 200 feet of visibility so appealing

that she wondered how to combine her love for the Middle Ages

with her new passion for diving. Maritime archaeology seemed

to be one way.

That led her to pursue a Master's degree in Maritime Archaeology

at East Carolina University in Greenville, North Carolina, which

offers one of three programs on underwater archaeology in the

United States. In the end, Zhenya successfully found a way to

combine the three passions of her life - history, maritime archaeology

and Jason, who also has made a career for himself in maritime

archaeology.

Last summer 2006, Zhenya made an exploratory trip to Baku to

try to understand the possibilities of maritime research in Azerbaijan.

In the future, she hopes that underwater archaeological projects

will again start up in the Caspian. The sea, she says, holds

so many secrets yet to be revealed. Contact Zhenya: anichenko@yahoo.com.

Footnotes

1.

Amu Darya is the longest river in Central Asia with a length

of 2,400 km (1,500 miles) of which 1,450 km (800 miles) are navigable.

Historical records state that in different periods, the river

flowed into the Aral Sea, the Caspian Sea or both. Source: Wikipedia:

Amu Darya, September 8, 2006.

2.

V.V. Bartold, Mesto prokaspiiskikh oblastei v istorii musul'manskogo

mira [The Place of the Caspian Region in the History of the Muslim

World] in Kaspiiski Transit [Caspian Transit], Moscow, 1996,

p. 263.

3. Khiva, a city in Uzbekistan, was described

by Muslim travelers in memoirs written in the 10th century. Archaeologists

assert that the city dates back to the 7th century. Wikipedia:

Khiva, September 8, 2006.

4. Bukhara is located in present-day

Uzbekistan. The historic center of the city is listed by UNESCO

as one of the World Heritage Sites. It contains numerous mosques

and "madrassas" [Islamic schools]. Wikipedia, January

25, 2007.

5.

L. Bagrow, "Italians on the Caspian," Imago Mundi,

Vol. 13 (1956), p. 2. According to Dr. Farid Alakbarli of Baku's

Institute of Manuscripts, the word Caspian derives from the name

of the Kaspi tribe, who lived in what is now southeast Azerbaijan

prior to the Christian era. Khazar (Khazar Danizi) is the Azeri

term for the Caspian Sea. In old Persian sources, it was sometimes

referred to as Hirkan (Hirkanian) Sea, a name designating the

vast forested region of Lankaran, which is located in southeast

Azerbaijan along the borders with Iran.

6.

Thor Heyerdahl (1914-2002), the well-known Norwegian explorer

and archaeologist, was convinced that early Scandinavians originated

from the Caspian region and found their way via water routes

to northern climes. See "The Azerbaijan Connection: Challenging

Euro-Centric Theories of Migration," by Dr. Thor Heyerdahl

in Azerbaijan International 3.1 (Spring 1995). Search at AZER.com.

7.

Yu. A. Karpychev, "Variations in the Caspian Sea Level in

the Historic Epoch," Water Resources, Vol. 28, No. 1, 2001,

p. 5.

8.

Mamedov, M.G. "Istoriya Dagestana s drevneishikh vremyon

do kontsa XIX veka" (History of Dagestan from Ancient Times

until the End of the 19th Century), Makhachkala, 1997, pp. 121-122.

9. Derbent is a city of the Republic of

Dagestan, Russia. It is the southernmost city in Russia and used

to be an Azerbaijani khanate, thus, today it is primarily populated

by Azerbaijanis. It claims to be the oldest city in the Russian

Federation with settlements dating back to 8th century BC.

10. Sabayil Rocks [sometimes spelled "Sabail"].

See "The Mystery of the Sunken Castle Sabayil: Many Questions

Still Plague Archaeologists" by Sakina Nasirova. Azerbaijan

International 8.2 (Summer 2000). For photos of the castle frieze

on display, see "The Shirvanshah Complex: The Splendor of

the Middle Ages" in the same issue. Search at AZER.com.

See additional articles in this

issue by Viktor Kvachidze's underwater archaeological explorations

of the Caspian Sea.

Early maritime archaeological expeditions carried out by Victor

Kvachidze near the Shulan Bay (northern coast of Absheron), 1969.

_____

Back to Index AI 14.4

(Winter 2006)

AI Home

| Search | Magazine

Choice

| Topics

| AI Store | Contact us

Other Web sites

created by Azerbaijan International

AZgallery.org | AZERI.org | HAJIBEYOV.com

|